Christians and Jews in Angevin England. The York Massacre of 1190, Narratives and Contexts. York Medieval Press 2013

Just before Easter in 1190, a group of poverty-stricken local lords and their followers, led by one Richard Mallebisse, forcibly entered the former residence of one of the wealthiest Jews in the city of York. They killed his widow and children and set the house ablaze. Upon discovery of this atrocity, many of the Jewish inhabitants sought refuge in the royal castle, bringing along their valuable possessions. Subsequently, the mob began to ransack the Jewish community, killing those who remained behind.

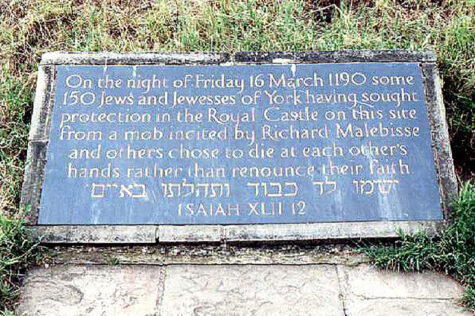

As chaos swept through the city, the group of frightened Jews within the castle refused the constable entry. In response, the Royal Governor ordered an assault on the castle. Although the governor later expressed regret, the enraged mob could not be deterred. During that night, the besieged Jews deliberated their fate. Ultimately, most of them chose to commit “Kiddush-ha-Shem,” a martyrdom in the name of God. The men took the lives of their own wives and children, while others destroyed their valuables. By morning, only a small number remained, opting to convert. They left the castle at dawn with a promise of safe passage, only to be slain by the angry mob. Overall, it is estimated that 150 Jews perished in this infamous massacre, which came to symbolize the heinous anti-Semitic persecution that had swept across Europe following the Crusades.

However, understanding the actions of the desperate Jews who collectively chose suicide and those of the furious mob that continued their pillaging remains a complex challenge.

As far back as 1974, Richard Barrie Dobson published a seminal study on the “Jews of Medieval York and the Massacre of March 1190,” later republished in a collection of his papers by Borthwick Institute Publications in 2010. Recent years have witnessed a surge of research uncovering the medieval settlement patterns, economic and social roles of Jews both within and outside their communities, their involvement in financing the Crown, and the religious context in which they existed.

Yet, the distinct nature of the 1190 York Massacre has made it difficult to integrate this event into the broader narrative. Is it a lens we must employ to comprehend the intricate and precarious lives of Jews in 12th and 13th century Angevin England? Or was it an extraordinary occurrence shaped by specific local circumstances in London and York at that time, including York’s de facto abandonment by the royal authority and the presence of increasingly impoverished minor lords burdened by rising royal taxes?

In 2010, a select group of scholars convened in York for a three-day seminar to revisit Dobson’s work and gain deeper insights into the context of the massacre. The collection of essays at hand reflects their overarching conclusion that the massacre in York was neither unique nor solely a local incident; it was, in fact, a pivotal event. This interpretation has been employed by the authors as a sort of entry point for comprehending the history of Jews in Angevin England.

Indeed, contemporaries recognized it as part of a larger pattern of egregious anti-Jewish persecution, which unfolded from Richard I’s coronation in London in 1189 through a series of towns and regions in subsequent months, culminating in York on a cold March night in 1190.

The opening three articles introduce us to the 1190 York Massacre, the affected neighbors and victims, and the series of attacks that swept through East Anglia and Lincolnshire in 1190. Another article delves into other manifestations of civil unrest. Alan Cooper notes that “extreme financial demands, rapid societal changes, and an increasingly unforgiving governmental apparatus created a nation fraught with anxiety and internal division.” Yet, is this explanation adequate? Could the event also be viewed as part of a pattern presented in a sequence of shaping narratives?

Nicholas Vincent asserts that contemporaries unequivocally regarded it as a “replay” of the Massacre of Masada in 73 AD, as recounted by historian Josephus in “The War of the Jews” from 75 AD. This historical account was widely available in libraries of that era. Although it remains unknown whether the Jews sheltered in the castle were familiar with the story, some of them likely were. Undoubtedly, William of Newburgh, the primary source for these events, was aware of and influenced by this story. Heather Blurton introduces another pre-existing narrative in her article, discussing biblical patterns found in the stories of the Exodus and the Babylonian Exile. She compellingly describes how these narratives shaped perceptions of Jewish-Christian relations, foreshadowing the ultimate expulsion in 1290.

A series of articles then examine the level of “convivencia,” or coexistence, between Jews and Christians. Through these articles, we gain insights into the practicalities of living side by side during a time of religious fervor and conducting business transactions. Abundant sources related to the needs of the royal administration of the 30 Jewish communities, which were living if not flourishing at that time, provide information on these interactions. Various articles offer a comprehensive introduction to the workings of this bureaucratic mechanism, as well as the day-to-day intricacies of business dealings between parties of differing faiths. Paul Hyams, in an intriguing albeit tentative article, explores this aspect.

Other articles delve into learned communities and the study of Hebrew, the operation of Talmudic communities in 13th century England, and the figurative roles Jews played in art and ecclesiastical literature of the era.

Concluding the collection are three articles that set the stage for understanding the massacre in contemporary times. These articles pose several at times uncomfortable questions: How should historians ethically and responsibly write about the events of 1190, considering that the act of committing “Kiddush-ha-Shem” remains relevant today? As is known, new recruits to the Israeli Army must ascend the winding ‘snake path’ to the summit of Masada to pledge their allegiance to defend Israel, vowing that “Masada shall not fall again.” This sentiment echoes the potential for history to repeat itself if Iranian Atomic Bombs wreak havoc across the Middle East. Given our knowledge of the 1190 York story, we immediately grasp the implications of this “Snake Path.” Regrettably, Hannah Johnson’s article on this topic is somewhat convoluted, omitting mention of both the modern Masada story and its ancient counterpart, even though these elements are prominent in the remaining articles. Instead, her piece outlines two historiographical methodologies and ethical stances. One approach acknowledges that the events in 1190 were in some ways both echoes and paradigmatic instances, while the other sees them as contingent occurrences, provoking ambivalence and uncertainty among scholars. Faced with these alternatives, her article strives to discern an appropriate ethical standpoint. Consequently, it raises a fascinating historiographical quandary and offers a remarkable introduction to the scholarly debates that have unfolded between these two perspectives during the latter decades of the 20th century. However, the article allows the author to somewhat elude the subject, affirming the necessity for ethical reflection without fully articulating its conclusions. There is undoubtedly more to be explored on this matter.

In fact, such exploration is indeed undertaken. In an article by Jeffrey Cohen titled “The Future of the Jews of York,” readers are transported into a dreamlike world, a medieval fiction, envisioning what could have been and what some hope might occur: a convivium with “others,” where goblets are not seized from hands but rather filled with wine and extended in hospitality.

Karen Schousboe

Christians and Jews in Angevin England. The York Massacre of 1190, Narratives and Contexts

Editor: Sarah Rees Jones and Sethina Watson

Contributors: Sethina Watson, Sarah Rees Jones, Joe Hillaby, Nicholas Vincent, Alan Cooper, Robert C. Stacey, Paul Hyams, Robin R. Mundill, Thomas Roche, Eva de Visscher, Pinchas Roth, Ethan Zadoff, Anna Sapir Abulafia, Heather Blurton, Matthew Mesley, Carlee A. Bradbury, Hannah Johnson, Jeffrey J. Cohen, Anthony Bale

York Medieval Press 2013

ISBN: 9781903153444

CONTENTS:

- Introduction: The Moment and Memory of the York Massacre of 1190

- Neighbours and Victims in Twelfth-Century York: A Royal Citadel, the Citizens and the Jews of York

- Prelude and Postscript to the York Massacre: Attacks in East Anglia and Lincolnshire, 1190

- William of Newburgh, Josephus and the New Titus

- 1190, William Longbeard and the Crisis of Angevin England

- The Massacres of 1189-90 and the Origins of the Jewish Exchequer, 1186-1226

- Faith, Fealty and Jewish ‘Infideles’ in Twelfth-Century England

- The ‘archa’ System and its Legacy after 1194

- Making Agreements, with or without Jews, in Medieval England and Normandy

- An Ave Maria in Hebrew: The Transmission of Hebrew Learning from Jewish to Christian Scholars in Medieval England

- The Talmudic Community of Thirteenth-Century England

- Notions of Jewish Service in Twelfth and Thirteenth-Century England

- Egyptian Days: From Passion to Exodus in the Representation of Twelfth-Century Jewish-Christian Relations

- ‘De Judaea, Muta et Surda’: Jewish Conversion in Gerald of Wales’s Life of Saint Remigius

- Dehumanizing the Jew at the Funeral of the Virgin Mary in the Thirteenth Century [c.1170 – c.1350]

- Massacre and Memory: Ethics and Method in Recent Scholarship on Jewish Martyrdom

- The Future of the Jews of York

- Afterword: Violence, Memory and the Traumatic Middle Ages

- Bibliography

READ MORE: